Disclaimer: The content of this blog is mine alone and represents my own views and opinions and does not necessarily reflect the views of the US Government, the Peace Corps, or the Ugandan Government. Furthermore, the intention of this blog is not to malign, injure, or libel, any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, or individual.

Photos and videos in this blog may not be reproduced without this bloggers expressed written permission.

Part Four: Pole Pole Ndio Mwendo

Week Sixty-Nine/ September 2017

The Peace Corps as Discourse Changing, Part One: A Brief Review of History, a Rewrite

The Rainy Season

I edited and re-wrote parts of my post from week nineteen (October 2016) of service.

…

Loucine Hayes, the former Peace Corps Uganda country director, wrote the following excerpt in a welcome letter sent to the 2016 Uganda Health and Agribusiness Peace Corps cohort several weeks before departure:

“This opportunity for service in Uganda can be among the richest growth experiences of your life, irrespective of background and age. It will be like nothing you imagine. The emptier your mind is of preconceived notions of the Ugandan people and the Peace Corps experience, the more likely this experience will be a positive one for you.”

Many volunteers are drawn to apply to the Peace Corps for not only what the Peace Corps offers, “it will be like nothing you imagine”, but what it represents, the Peace Corps Volunteers handbook states, “(The Peace Corps) represents something special. It is a unique government agency that best reflects the enduring values and ideals of the American people: generosity, civic pride, a strong work ethic, and a commitment to service.” Before departure, during training, and throughout service, Peace Corps volunteers are encouraged by staff to be introspective, open-minded, and gracious, as volunteers are supposed to represent, “something special.”

Nevertheless, the Peace Corps is a challenging program “(it’s) the toughest job you’ll ever love” (The Peace Corps AdCouncil). Service lasts for two years and volunteers are put into unfamiliar situations where they are cultural outsiders, don’t speak the language, face harassment, are far from their friends and family, and in many cases, volunteers are put in countries where they are hyper visible for the first time. Volunteers endure immense stress, unimagined hardships, and often, loneliness; in addition to their positive experiences. Throughout service volunteers are asked to be open, flexible, and recognize cross-cultural clashes; however, in the face of often overwhelming challenges, the question may be asked, how do volunteers process their experiences, both internally and verbally.

When navigating their changing sense of agency and structure, volunteers do not come in without any preconceived notions, nor can they rid their mind of preconceived notions prior to coming, as Loucine asked. Schemata, a script, “a set of expectations and projections that instruct us on what to expect” (Chamberlain loc. 5617), are built through the process of enculturation that every individual undergoes within their societies; meaning, volunteers are not navigating their agency and structure as blank slates, volunteers are navigating these new relationships with deeply rooted preconceived notions about the people of Uganda.

All volunteers are US citizens, and most volunteers were raised in the US. Therefore, for many volunteers their enculturation process involved forming relationships with their own agency and structure in an institutionally racist society. Moreover, for many volunteers, their experience in the Peace Corps, particularly volunteers in Uganda, is their first experience with being hyper visible. Volunteers are noticed because they look different, not because of what they studied in college, or their last job, volunteers are noticed because they look different than a large number of people in the country in which they are serving. Volunteers, are often given unwanted attention because they are hyper visible. Therefore, what schemata do they have to fall back on when they have negative interactions with Ugandans, schemata filled with the devaluation of black people, and a patronizing approach in navigating relationships.

If language plays a key role in constructing reality, and therefore, culture, how can volunteers use more language, rather than less, to deconstruct and adjust their schemata. Essentially, how can we, as Peace Corps Volunteers, address and deconstruct what it means to be, in many cases, a white volunteer from an institutionally racist country serving in sub-Saharan Africa in a former British colony, so that we are able to more effectively serve and understand and value the lives and realities of the Ugandans with whom we live and work.

Moreover, how can the existing Peace Corps cultural hegemony be adjusted to facilitate these deconstructions. I posit that by defining more language that can be used to describe cross-cultural clashes, in this essay just three common schemata, in terms of a cultural anthropological approach to communication, according to the work of Dr. Edward Hall, it may serve as a tool box for volunteers to better assign vocabulary to their experiences and define them beyond the surface-level, so that we are able to be more gracious reflexive agents of the cultures around us. Moreover, I also believe that in order to frame the discussion of these three schemata, it is vital it also briefly address colonialism, the relationship between colonialism and the volunteer industry, and the current climate of the US as an institutionally racist society, to understand that we are not autonomous agents in thought and interaction with others, we are deeply informed by the hegemonic discourses of the United States and volunteer culture once in Uganda. Even if we feel that we were somehow separated from racially-motivated violence in the US because of where we lived, the communities that allow us to think that we were somehow separated from the violence endured by people of color, is in itself indicative of the complicity in the institutionally racist structure. No one is exonerated from desperately needing to be a part of this conversation however uncomfortable. Well-intentioned willful-ignorance out of a desire to stay comfortable with our own sense of self, negativity impacts the livelihoods of people of color.

Finally, I believe that one of the most valuable aspects of Peace Corps is that it provides an avenue for volunteers to imagine and live within a different society. Peace Corps, especially Peace Corps Uganda, provides an unmatched opportunity for volunteers to adjust and rewrite their schemata in a different cultural setting. Volunteers have the opportunity to have black role models, black peers, black teachers, black representation in the media; and to therefore, rewrite a different discourse; where black skin and natural black hair is beautiful, and where black people are intelligent, professional, and capable of solving the problems that so many foreign volunteers flock to try and solve themselves.

I would also like to note that I am not an expert, I am simply writing as a curious Peace Corp Volunteer reflecting on my service.

“No matter your complexion, we all have skin in the game of race relations, and we need to get it right.” Rev. Dr. A. Roy Medley, ABCUSA

A Brief Review of History

Addressing our history and the interplay between history and our role as volunteers is crucial for understanding ourselves as mirrors of our culture. One may start with the questions of, why are you here? Why Sub-Saharan Africa? Why not Southeast Asia? Or Eastern Europe? Or parts of the US? In deciding to come to Uganda, much of the what many Americans know about sub-Saharan Africa, is based off of literature and media portrayals of Africans by non-Africans; which follows in a long history of the US and European countries representing the “other.”

In his book Orientalism, Edward Said, while largely focusing on the middle-east, nonetheless begins his work be explaining Orientalism in broad terms, ie, the Orient as all of the colonies of Europe and the US (Said 4). Edward Said uses the term Orientalism to encompass the what the colonizers framed the difference between “us” and “them”, “Orientalism (is) a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient.” (Said 3) This domination meant not only the act of colonizing, (which was often justified, not only on economic, but also on moral grounds) but also through the production of literature, theatre, scholarly work, and university areas of study about the Orient as produced the colonizers, “Knowledge of the Orient…(is) something one studies and depicts (as in a curriculum), something one disciplines (as in a school or prison), something one illustrates (as in a zoological manual).” (Said 40) Moreover, the colonizers constructed knowledge about the Orient, “(Colonizers made) Orientalism, as a system of knowledge about the Orient, an accepted grid for filtering through the Orient into Western consciousness-the statements proliferating out from Orientalism into the generic culture.” (Said 6) Meaning, the material and knowledge constructed by the colonizers in regard to their colonies was the knowledge that permeated popular culture in the 18th and 19th centuries; therefore, constructing a view of the Orient dominated by the US and European frameworks (Said 40).

One of the methods by which colonizers justified colonialism was on, what they claimed to be, moral grounds. The United States and many European countries argued that the dominated countries in question were incapable of governing themselves, and inherently savage and immoral, “The Oriental is irrational, depraved (fallen), childlike, “different”; thus, the European is rational, virtuous, mature, and “normal’” (Said 39).

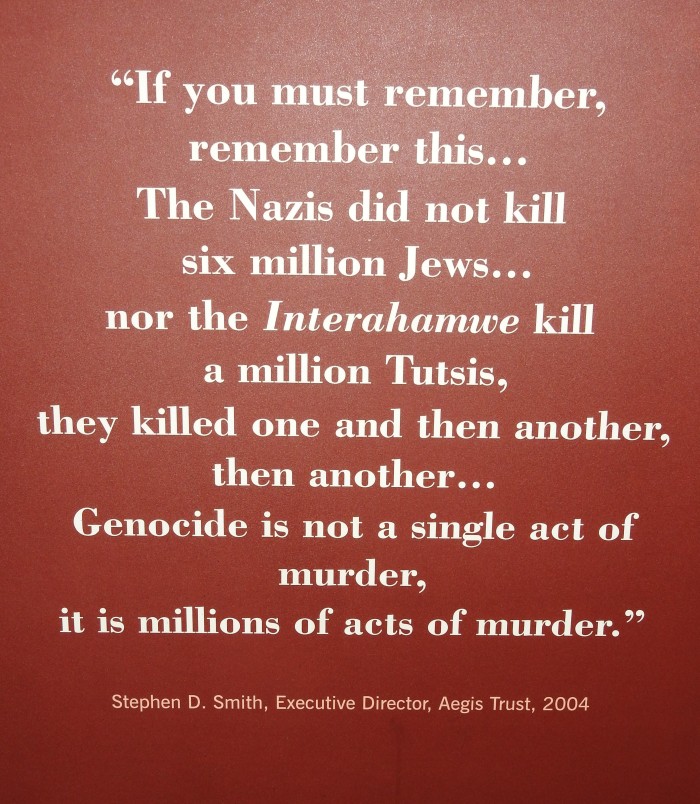

Furthermore, a fundamental aspect of the colonizers argument was race, “the Atlantic slave trade, did not have a purely economic rationale; rather is produced political structures as well as social representations of humanity that were ordered and ranked (Patterson 1982 as cited by Chaney, et al. 79) Many different disciplines, such as biology, philosophy, and theology, sought to explain in pseudo-scientific terms why some races were more primitive then others. It is during the nineteenth century, the field of eugenics flourished, and during the twentieth century, that more laws were put into place to institutionalize white supremacy, “During this period, theological and scientific elements could be combined in the process of making racial categories and educating the human senses to see race and normalize white supremacy.” (Chaney, et al. 81) By 1914 Colonial powers dominated 85% of the world. (p. 41) From the reasoning created during the Atlantic slave trade, to King Leopold’s genocide in the Congo, the Holocaust in Europe, to Jim Crow Laws, and Apartheid, the past several hundred years have sought to portray black people as incompetent and immoral, to therefore justify white supremacy (Chaney, et al. 83). Additionally, during the last several hundred years the US and European countries have been the dominant producers of literature and policy and the writers of history, the producers of culture and reinforcers of structure.

Thus, while Apartheid and Jim Crow Laws have ended, popular discourse still reflects a culture permeated by colonial-rooted notions of white superiority. The US is still producing portrayals of sub-Saharan Africans and filtering them into the consciousness of Americans, instead of those people living in sub-Saharan Africa representing themselves in the US media and in US literature. Moreover, these portrayals still produce images of Africans as incompetent. In the book, White Man’s Burden by William Easterly, he provides an excerpt of a 2004 speech by Stanford political scientist Stephen Kranser. Kranser stated, “Left to their own devices, collapsed and badly run governed states will not fix themselves…To reduce international threats and improve the prospects for individuals in such polities, alternative institutional arrangements supported by external actors, such as de facto trusteeships and shared sovereignty, should be added to the list of policy options.” (Stephen Krasner as cited by Easterly 270) While not explicitly colonialism the excerpt clearly suggests the patronizing attitude that the nations are unable to govern themselves; however, “Today’s nation builders would claim that they are more altruistic.” (Easterly 278)

It is not only in policy suggestion that the devaluation of black individuals and a patronizing attitude is present among US individuals. According to a 2015 PBS study in the United States, 51% of white men surveyed stated that they thought black people were lazy and 43% white men surveyed thought that black people were less intelligent; furthermore, “These racial disparities are perpetuated not only through explicit discrimination, but through the power of history.” (Mcelwee). Who writes history books? Who teaches history in schools? Moreover, not only are black men disproportionately incarcerated, but even black individuals who graduate from elite schools still have fewer job opportunities and a lower starting pay (Mcelwee). Here we can clearly ask ourselves, who is doing the hiring? And what history and discourses have informed their decision-making?

Additionally, black individuals are often portrayed negatively in the media, and are given disproportionate media attention when the news story relates to poverty and crime (The 2011 The Opportunity Agenda cited by Mcelwee). “These portrayals… in print media, on television, the internet, fiction shows, print advertising and video games, shape public views of and attitudes toward men of color. They not only help create barriers to advancement within our society, but also ‘make these positions (homeless and drug-dealers) seem natural and inevitable.’” (Leigh) Therefore, in relation to the Peace Corps, before volunteers begin their service, the public representations of black individuals they have seen are not of professionals but of unintelligent degenerates who need to be controlled, all too often through policy and force.

According to the NAACP, “African Americans are incarcerated at more than 5 times the rate of whites.” Yet, “African Americans and whites use drugs at similar rates, but the imprisonment rate of African Americans for drug charges is almost 6 times that of whites.” (NAACP) Moreover, any discussion of Black Lives Matter, unequal education or employment opportunities, and young black men being disproportionately killed by police, in fact, the “rate of death for young black men (killed by US police officers) was five times higher than white men of the same age” (Swaine, et al) is stifled. I also recommend reading the following article: http://www.theroot.com/open-letter-to-white-people-who-are-obsessed-with-black-1790856298

How can Peace Corps volunteers utilize their understanding of history and culture, combined with their experiences as a volunteer to raise an awareness of different narratives?

In the US, both overt acts of racism and the broad institutional racism, permeate society. For those willing to discuss is, I think many individuals are happy to discuss racism without reflecting upon their own behavior or how they may, whether aware of it or not, be contributing to systemic oppression. Kenyan-American writer, Teju Cole, wrote an excellent piece in 2012, titled, “White Industrial-Savior Complex”, in which he discusses both racism and discussions of race in the US today, and the role of volunteers in countries, like Uganda:

“There is an expectation that we can talk about sins but no one must be identified as a sinner: newspapers love to describe words or deeds as “racially charged” even in those cases when it would be more honest to say “racist”; we agree that there is rampant misogyny, but misogynists are nowhere to be found; homophobia is a problem but no one is homophobic. One cumulative effect of this policed language is that when someone dares to point out something as obvious as white privilege, it is seen as unduly provocative…the effect of this enforced civility is that those voices are falsified or blocked entirely from the discourse.” (Cole)

People do not want to be called a racist, therefore how does this play out with white individuals who decide to volunteer in sub-Saharan, Africa?

Prior to serving as a volunteer, many soon-to-be-volunteers, spend their whole lives exposed to the discourse of black individuals as unintelligent, racially inferior, and not fit to hold positions of prestige within society. Moreover, there is the added complexity of what is commonly referred to as the “white savior complex” a patronization of Africans, spawned from colonialism, in the volunteer culture of some individuals who chose to volunteer in sub-Saharan Africa. Volunteering is an industry, and the advertisements for the industry, which filter images of the ‘other’ into US consciousness, usually include colonial sentiments, such as, “Come and Do Good.” “Help the Poor Children of Africa” or “Only You Can Make a Difference.” I have heard volunteers refer to the Africans with whom they interact as their “children”, posting photos with them, the white volunteer, dressed in “exotic African clothing” surrounded by children. Local residents and communities are often mistreated in the name of ‘doing good’, but doing good is often doing a great deal of unintentional harm, “[f]rom orphanage tourism, to blatant racism in [the] treatment of local residents, to trafficking children in the name of adoption – the list of errors never ends” (Zane). Volunteers ought to treat local residents with respect, dignity, and professionalism “for example, nurses in America are not allowed to take Instagram photos of their patients and post emotionally captivating blurbs about how tragic their life is.” (Zane) Yet this happens once the individual is out of the US and “helping in Africa,” a statement I hear all too often. There is still a deeply engrained patronization of Africans in volunteer culture that is deeply seeded in colonialism.

What is so tragic about the so-called “White Savior Complex” is how acceptably it is portrayed, both historically, in its close relationship with colonialism, and today. However, I would like to add that there is nothing wrong with wanting to make the world a better place and learn about other places and peoples; however, what needs to be added to the discussion is what does it mean to “make a difference,” by examining why one would want to volunteer in a place like sub-Saharan, Africa, maybe it should be changed to “shut up, listen, do nothing, try and do no harm, try something, do no harm.” Do no harm, there is the important idea that those who are being helped ought to be consulted over the matters that concern them.” (Zane) Again, in his brilliant piece, “White Industrial-Savior Complex” Teju Cole, elaborates on the discussion of “making a difference.”

“One song we hear too often is the one in which Africa serves as a backdrop for white fantasies of conquest and heroism. From the colonial project to Out of Africa to The Constant Gardener and Kony 2012, Africa has provided a space onto which white egos can conveniently be projected. It is a liberated space in which the usual rules do not apply: a nobody from America or Europe can go to Africa and become a godlike savior or, at the very least, have his or her emotional needs satisfied. Many have done it under the banner of “making a difference… there is an internal ethical urge that demands that each of us serve justice as much as he or she can. But beyond the immediate attention that he rightly pays hungry mouths, child soldiers, or raped civilians, there are more complex and more widespread problems. There are serious problems of governance, of infrastructure, of democracy, and of law and order. These problems are neither simple in themselves nor are they reducible to slogans. Such problems are both intricate and intensely local.

How, for example, could a well-meaning American “help” a place like Uganda today? It begins, I believe, with some humility with regards to the people in those places. It begins with some respect for the agency of the people of Uganda in their own lives. A great deal of work had been done, and continues to be done, by Ugandans to improve their own country, and ignorant comments (I’ve seen many) about how “we have to save them because they can’t save themselves” can’t change that fact.

“Let us begin our activism right here…To do this would be to give up the illusion that the sentimental need to “make a difference” trumps all other considerations. What innocent heroes don’t always understand is that they play a useful role for people who have much more cynical motives. The White Savior Industrial Complex is a valve for releasing the unbearable pressures that build in a system built on pillage. We can participate in the economic destruction of Haiti over long years, but when the earthquake strikes it feels good to send $10 each to the rescue fund. I have no opposition, in principle, to such donations (I frequently make them myself), but we must do such things only with awareness of what else is involved. If we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement.” (Cole)

Better informing ourselves of our colonial history, current discussion of racism in the United States, and the relationship between colonialism and the volunteer industry, can help us to better understand the structures that have informed our schemata. We are deeply informed by the discourses of the United States, and that is something we need to come to terms with. However, I believe that one of the most valuable aspects of Peace Corps is that it provides an avenue for volunteers to imagine and live within a different society so that we may adjust our schemata. Volunteers have the opportunity to have black role models, black peers, black teachers, black representation in the media; and to therefore, rewrite a different discourse; where black skin and natural black hair is beautiful, and where black people are intelligent, professional, and capable of solving the problems.

Citations

Chamberlain, Robert. An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2016.

Chaney, David, et al. Cultural Sociology: An Introduction, 2012.

Cole, Teju. “The White Savior-Industrial Complex.” The Atlantic. 21 March 2012. http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/

Donaldson, Leigh. “When the media misrepresents black men, the effects are felt in the real world.” The Guardian, 12 Aug 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/aug/12/media-misrepresents-black-men-effects-felt-real-world

Easterly, William. The White Man’s Burden, 2006.

Mcelwee, Sean. “The Hidden Racism of Young White Americans” PBS Newshour, 24 March, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/americas-racism-problem-far-complicated-think/

“Criminal Justice Factsheet.” NAACP. 2017. http://www.naacp.org/criminal-justice-fact-sheet/

Said, Edward. Orientalism, 1978.

Swaine, Jon; Laughland, Oliver; Lartey, Jamiles; McCarthy, Ciara. “Young black men killed by US police at highest rate in a year of 1,134 deaths.” The Guardian. 31 December 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/dec/31/the-counted-police-killings-2015-young-black-men

Zane, Damian. “Barbie challenges the ‘White Saviour Complex’.” BBC News. 1 May 2016. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-36132482

“1961-1991 The Toughest Job You’ll Ever Love.” AdCouncil Peace Corps . 2016. http://www.adcouncil.org/Campaigns/The-Classics/Peace-Corps